![Georg Brandes (1842-1927) [Source: http://denmark.dk/en/meet-the-danes/great-danes/scientists/georg-brandes/]](http://www.peterhfrank.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Georg_Brandes_by_Szacinski580.jpg)

Georg Brandes (1842-1927)

Many years ago, I was driving through the suburbs of Dallas on a quiet weekend when I saw a big sign announcing a book sale under a large white tent in a parking lot. It was a fundraiser of some sort and they had rows and rows and rows of books that were no longer wanted from some library or school or someplace else I don’t remember.

With no place to be and moving as slowly as possible on a typical, scorching, sunny day, I wandered each aisle and carefully studied thousands of spines. And there it was: What Nietzsche Taught – a book by Georg Brandes, a brilliant Danish scholar from the late 19th century who had been an acquaintance of Ibsen and probably most of the Scandinavian and German intellectuals of the time. He had also corresponded with Nietzsche and introduced his philosophy to much of Europe. In fact, Brandes was probably the first guy who suggested to Nietzsche that he become familiar with someone named Soren Kierkegaard. He was also the person to whom Nietzsche wrote one of the greatest letters of all time. One of the so-called “madness letters” that Nietzsche composed in Turin during a brief period in early January 1889 and never mailed, the unstamped letter to Brandes said:

“To the friend Georg,

“When once you had discovered me, it was easy enough to find me: the difficulty now is to get rid of me…

[Signed] The Crucified.”

So how did this treasure, apparently the first English edition, sit there unnoticed and sell for just a few dollars? Because someone (who might want to try reading their own books a bit more) had placed this fine edition in the section about Education. That’s right. Where else would you put a book titled What Nietzsche Taught?

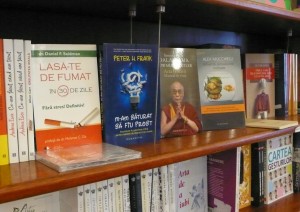

Now before I go on, let me absolutely assure you that I’m not suggesting any parallels between Friedrich Nietzsche and me. He had a lot more hair. And, I’m told, he successfully completed his “Introduction to German” course. But that said, not since that day in Dallas have I noticed a book so misplaced, so oddly juxtaposed with unrelated subjects, until recently when I saw my own published scribblings about critical thinking in business in a Carturesti bookstore placed between a book on how to quit smoking and one by the Dalai Lama. That’s right. Snuggled together. Like best friends hanging out with no place to go.

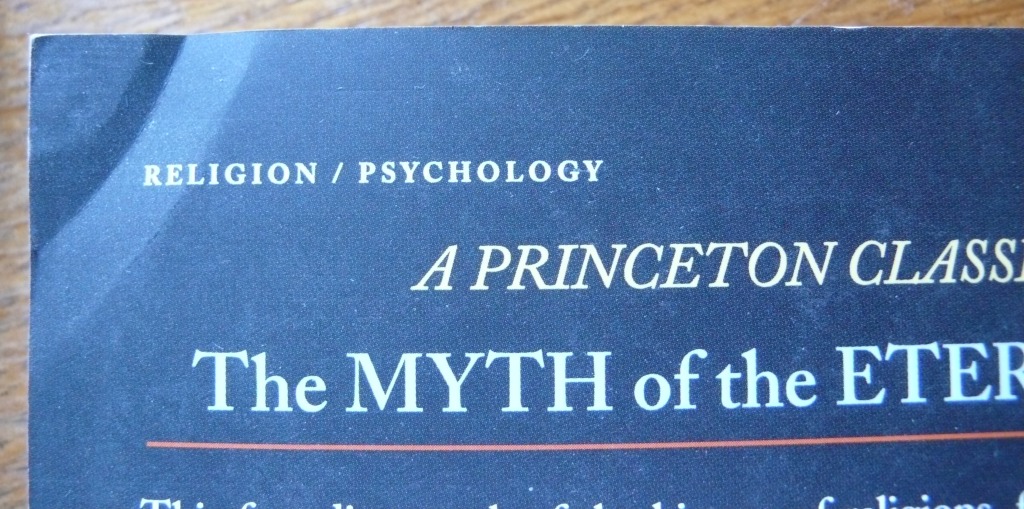

The Myth of the Eternal Return

I’m not sure about you, but when I think about me (or my writing), only seldom does the Dalai Lama come to mind (though it does frequently make me want to quit quit smoking). In fact, I would guess that the Dalai Lama (Note to Editor: is he known as just Lama on second reference?) and I have about as much in common as Nietzsche and I. Yes, we each have written a few things. But I would hardly expect that single similarity to warrant our being put on the same shelf – or even in the same store.

Frog and Toad Together

You can’t really blame the bookstores and I’m not complaining. I’m just glad my book exists. But I do feel sorry for the retailers and their clerks who are confronted by the dozens of books that are published here every single day. Who has time to sort them all out? Just because you sell them doesn’t mean you read them. (I mean, I’ve served Sautéed Cerveaux and I’ll be damned if I’d eat one.)

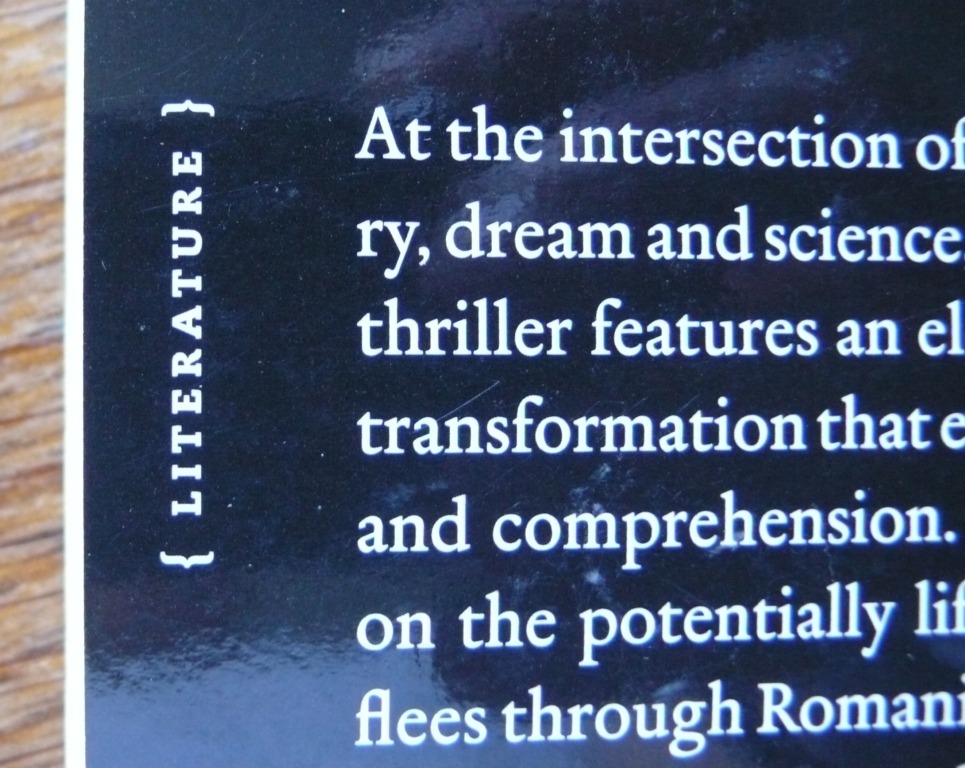

some other book

So why don’t publishers here bother telling anyone what their books are about? For the same reason, I suppose, employees in restaurants and the places we shop are not taught by their managers to say “Hello,” “I’ll be right there,” and “Ok, I’m back from my nap. Did any of you want another drink?” I guess they take for granted that we know that’s what they’re thinking. Understand, it’s not just my book and it’s not just one publisher that believes it unnecessary to tell others the secret topic that’s hidden within their pages. Maybe they just take for granted that the bookstores will figure it out. They think it’s the other guy’s job. Perhaps they do this because they don’t like them. I’m told publishers here don’t bother communicating much with bookstores – except when they try unsuccessfully to get paid. But that’s the great thing about print, whether selling or writing. You don’t actually have to talk to anyone.

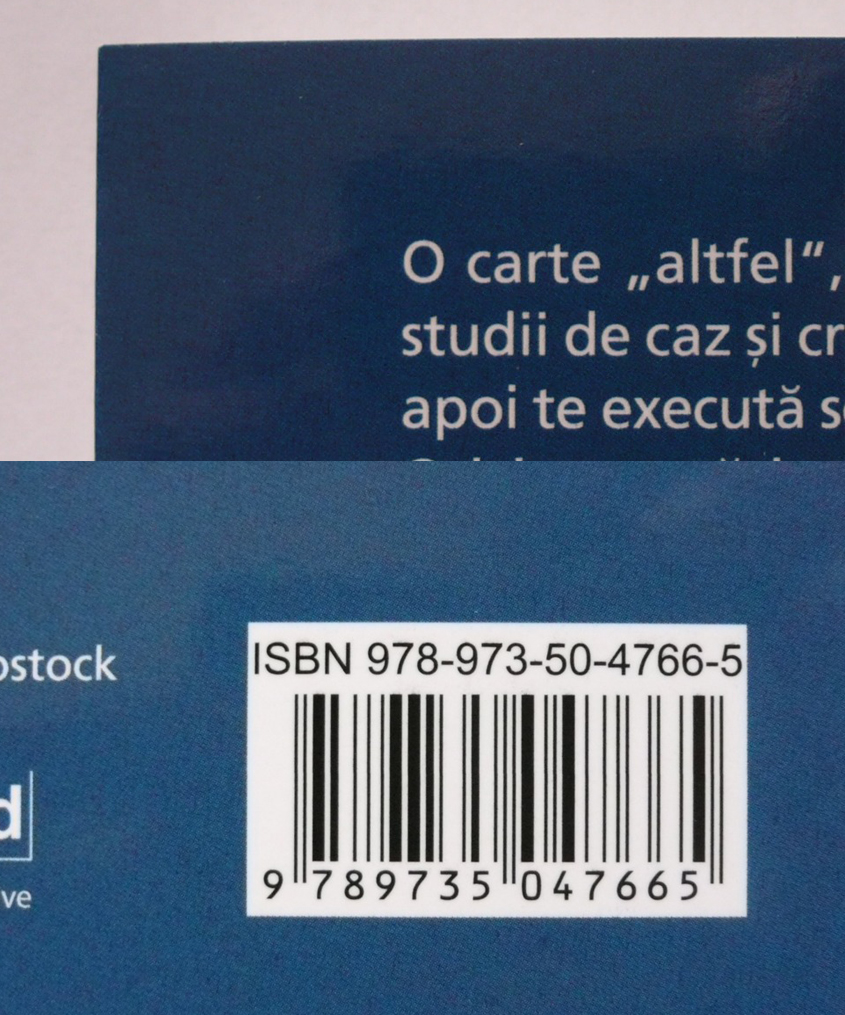

Now for those of you who don’t read English, let me tell you that it’s almost impossible to find a book printed in English, whether in the UK or the US, that doesn’t somewhere on the jacket or flaps list the category of the subject of what’s written inside. Even the Bible, I suspect, has “Religion” printed somewhere on the back. (Yes, ok, some might suggest “Fiction,” but that’s the subject for someone else’s completely different blog.)

Indeed, I’m told that somewhere between 90 and 120 percent of all books published here are imported and translated from English. So the obvious question is: why not import this idea from the cover as well?

An Anxious Age

So this little curiosity got me paying attention. And what fun it has been. There is the Dictionary of Sociology directly under a sign for Economics. The autobiography of Jung is in Philosophy with Kant and Aristotle while the other books by Jung are five feet away in the Psychology section. In Sociology, of course, are put all of the books no one knows where else to put them (sort of what happens in the real world also). I had the feeling that if I kept looking, I’d probably find Who Moved My Cheese? in the Cooking section. Or Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance under Do-It-Yourself. Maybe The Magic Mountain in Tourism with other books about Disneyland.

?

Instead, though, I concentrated on my book. (After all, if I don’t, who will?) That book I’ve found in Practical Psychology. Sometimes Self-Help. Other times safely placed under a section dedicated to the publisher. For a while it was placed generally in New Books. Other times, it’s on some table that’s completely unmarked. And my favorite is when the manager says they have it, but no one knows where.

The sad fact is that I originally worried I would have to convince people my book was not only about business. Now I find I need to convince them it is.

Finally, though, I did find it in the Business section. Oddly, it was also at a Carturesti, but a different one in town. This time, it was placed between Sheryl Sandberg’s Lean In and James Carville and Paul Begala’s book titled Pupa-I In Bot Si Papa-I Tot. Manual De Marketing Politic (which means something like Kiss His Mouth And Eat All Of Him. A Manual Of Political Marketing).

What?!?!! On second thought, nevermind. Could you please put it back next to my friend Mr. Lama?

![Georg Brandes (1842-1927) [Source: http://denmark.dk/en/meet-the-danes/great-danes/scientists/georg-brandes/]](http://www.peterhfrank.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Georg_Brandes_by_Szacinski580-e1441785391268.jpg)